When I sat down to write this post, I found myself asking: how should I begin? Should I start with the story of why Nicosia is divided? Perhaps with the events of 1974, the intervention, the tears and tragedies, the politics and endless dramas.

But then I wondered, why? Why not, instead, focus on the unique charm of this divided capital? On one side, the bustling cafés and boutiques of the Greek Cypriot south; on the other, the Ottoman-era caravansaries, the winding bazaars, and the narrow, alluring alleys of the Turkish Cypriot north. Why not celebrate the chance to experience two worlds that both radiate the warmth of Cypriot hospitality, all without ever leaving the same city?

Why dwell on borders that alienate, that fuel hostility, when one could imagine them turned into a soccer field, spreading joy and positive energy instead?

So yes, that is what this post will be about. Without further ado, let’s get teleported to Nicosia, Cyprus’ divided capital.

After a full day exploring Varosha, then Gazimağusa, and finally Ancient Salamis, passing through Muratağa, Sandallar, and Atlılar, we reached Nicosia by evening. By then, after driving across the island for a day, I had grown accustomed to having the steering wheel on the right side of the car, and to my surprise, I was actually enjoying it. That said, downtown Lefkoşa (Turkish part) isn’t exactly super car-friendly: narrow streets, missing or misleading traffic signs, and haphazard parking make driving there a bit frustrating. Still, the city more than makes up for it on foot. Lefkoşa is wonderfully pedestrian-friendly, with plenty of hidden gems waiting to be discovered.

Since the city is divided by the Green Line, I’ll refer to the Turkish side as Lefkoşa and the Greek side as Nicosia.

One of the first things you notice in Lefkoşa is that it feels somewhat underdeveloped, a contrast that becomes even clearer once you cross into the Greek side. In the heart of the old town, many houses are still fairly well maintained, but as you wander into other neighborhoods, the atmosphere shifts and can feel a bit rundown. This isn’t entirely surprising, given that the Turkish side remains unrecognized by the international community, limiting its ability to open itself up fully to the world.

However, don’t get me wrong. There are still plenty of Instagram-worthy streets and views. In fact, that worn, old-world character adds a special charm when you’re trying to capture the soul of the city’s historic lanes.

The Green Line separating the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) from the Republic of Cyprus is still patrolled by both Turkish and UN soldiers. Caution is advised when approaching it from either side. Even if it feels quiet and deserted, rest assured, it’s always under watch, with numerous cameras monitoring the area. In most places where there’s a military presence, photography is strictly prohibited.

There are certain spots in Lefkoşa that you simply shouldn’t miss, and one of the most unique experiences awaits you right along the border itself. Imagine sitting down with a steaming cup of tea and a slice of rich, homemade cake, all while being literally a few steps away from the Green Line. It sounds surreal, but that’s exactly what you can do.

Zahra Street is the perfect place to pause after a long day of exploring. The atmosphere here blends the energy of two worlds, offering a front-row seat to both the North and the South. As you relax, you can watch the rhythm of daily life unfold on either side, all framed by the soft golden glow of the Mediterranean sunset.

The Island of Cyprus remained under Ottoman rule for more than three centuries, and the legacy of that era is still visible in many of the island’s historic landmarks. Among the most iconic is Büyük Han (“The Great Inn”) in Lefkoşa. Built shortly after the Ottoman conquest, it originally served as a caravanserai, a roadside inn that provided shelter, stables, and space for merchants journeying across the island. Today, after elaborate restoration, Büyük Han has been transformed into a lively cultural hub, home to art galleries, artisan workshops, souvenir boutiques, and inviting cafés.

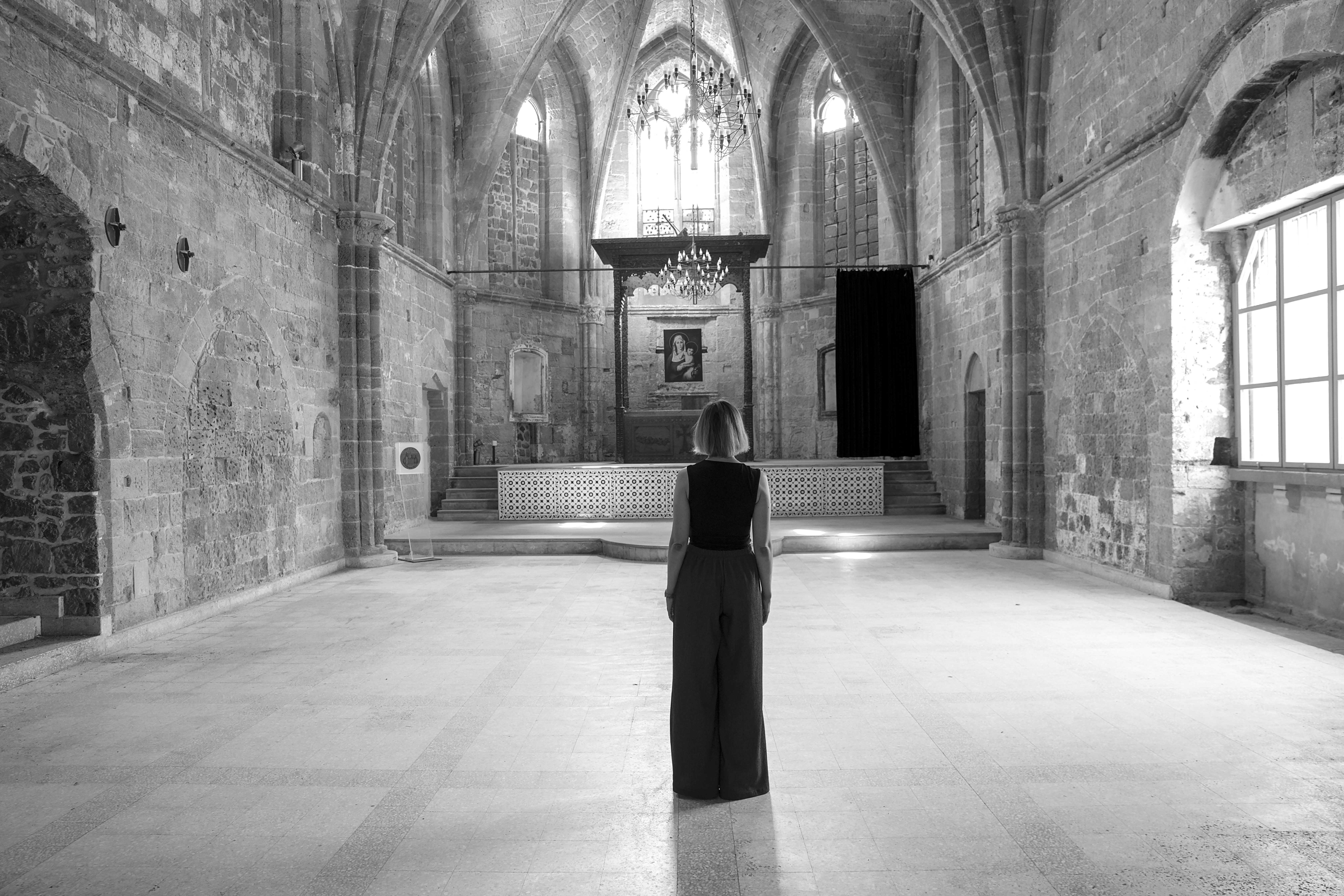

Greek Orthodox Christianity and Sunni Islam are the two dominant religions on the island, but Cyprus is also home to smaller communities, including Armenian, and Latin Catholics. The Armenian Church of Our Lady of Tyre is a notable example of this heritage. Restored by Republic of Turkey, it is open to all visitors for free, it provides a wonderful opportunity for photographers to capture both its architectural beauty and its serene atmosphere.

A lot of people think crossing from the Turkish side to the Greek side of Cyprus is difficult, but from our experience, it’s actually extremely easy. If you’re using a Turkish passport, you might be denied entry, but if your passport allows visa-free access to the Schengen area, there’s usually no problem. Turkish Cypriots can also cross to the Greek side with just their ID cards.

We used the Lokmaci Crossing (Ledra Street Crossing), and it was super quick and convenient. Since it’s been open 24 hours since 2008, you don’t have to worry about returning to your side of the island. The officers on both sides were very friendly, and you could cross back and forth as many times as you want without any issues.

One thing I learned to keep in mind: your passport usually allows you to stay on the island for 90 days, and since the Greek side doesn’t officially recognize the Turkish part, the time you spend in the TRNC counts toward that limit. Also, there are no visa stamps when entering or leaving through this crossing, which makes everything feel very smooth and hassle-free.

The moment you step onto Ledra Street, it initially feels like a continuation of Girne Caddesi, yet it quickly reveals its own character, modern, lively, and bustling with people, shops, restaurants, and cozy cafés. You might wonder what that old British mailbox is doing on the side of the street. Well, it’s a reminder that the United Kingdom ruled Cyprus for over eighty years. While their presence on the island is now limited, traces of British influence are still visible everywhere. Interestingly, although Ledra Street feels peaceful and lively today, it was once nicknamed “Murder Mile” because of frequent attacks on British colonial forces.

Oh, if you’re craving delicious food at a reasonable price, I highly recommend stopping by Avo Armenian Food. It’s the perfect spot to enjoy fresh lahmacun and authentic Georgian bread, a real treat for your taste buds.

The Greek side of the island appears much more organized and wealthy compared to the Turkish side. Yet one thing that struck me was that, while I expected to feel like I was in the Republic of Cyprus, the atmosphere felt much closer to Greece itself.

No matter which corner you turn on the Greek side, you’re bound to see Greek flags waving proudly. The same goes for the Turkish side, with Turkish flags visible everywhere. It seems that, after all these years since the division, both communities have grown closer to their respective guarantor countries.

While religion doesn’t have a major influence in Northern Cyprus, the Greek Orthodox Church remains quite influential in the southern part of the island. The Church of Cyprus complex, situated not far from Ledra Street, is particularly striking, and the ceiling of the Apostle Barnabas Cathedral is truly a feast for the eyes.

One interesting thing you’ll notice in Lefkoşa or Nicosia is that many mosques look a bit different from those in other Muslim countries. That’s because most of them were converted from churches during the Ottoman era. From the outside, they still retain much of their original church-like appearance, but inside, they serve as functioning mosques. The one in the picture is Omeriye Mosque in Nicosia, while the largest is Selimiye Camii in Lefkoşa. Originally built as Saint Sophia Cathedral, it was converted into a mosque following the Ottoman conquest of Cyprus in 1571, and it remains a mosque to this day.

Cyprus has a remarkably long and layered history, having been ruled in turn by the Romans, the Byzantine Empire, the Lusignan dynasty, the Venetians, the Ottomans, and finally the British before gaining independence in 1960. Each of these powers left behind traces of their presence, fortresses, churches, mosques, and colonial buildings, that still shape the character of the island today. For anyone curious to dive into this past, the Cyprus Museum in Nicosia offers an excellent starting point, where you can admire artifacts spanning thousands of years, many of them accessible free of charge.

Another landmark that has played a defining role in the island’s character, and one you definitely shouldn’t miss is the Paphos Gate. Constructed in 1567 by the Venetians, it formed part of the mighty fortifications encircling Nicosia, built to protect the city against the advancing Ottoman forces.

Since Northern Cyprus is administered by the Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus, you’ll come across municipal buildings in Nicosia that symbolically represent towns located on the Turkish-controlled side of the island. One that particularly caught my attention was the “Kythrea – Değirmenlik” city hall.

You won’t find many tall skyscrapers or towers in Nicosia or Lefkoşa, which, in a way, helps preserve the authentic character of the city. Still, if you’re after a panoramic view of both sides, the Shacolas Tower Museum and Observatory is an option. The observation deck sits on the 11th floor, and entry costs just €2.50. The attendant there wasn’t exactly the friendliest during my visit, but honestly, the view alone is probably worth the price.

Before wrapping up, I want to share two places that left a deep impression on me. On our way to Lefkoşa, we passed through the villages of Atlılar, Muratağa, and Sandallar, where in 1974 around 126 Turkish Cypriot civilians, including women, children, and the elderly were massacred by Greek Cypriot paramilitary forces and buried in mass graves.

The other site I want to briefly highlight is the Barbarlık Müzesi in Lefkoşa. On the night of 24 December 1963, during the period known as “Bloody Christmas”, Greek Cypriot paramilitaries attacked the home of Dr. Nihat İlhan, a Turkish Cypriot doctor. His wife, Mürüvet İlhan, and their three young children, aged 6, 4, and just 6 months were brutally murdered, along with a visiting neighbor. They had been hiding in the bathroom when they were shot, and the bloodstains from that tragic night are still visible today, making the museum a haunting reminder of the violence endured by Turkish Cypriots.

The two communities in Cyprus have lived separately since 1974. In 2004, UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan proposed a plan for reunification, known as the Annan Plan, which offered a federal solution under a single United Republic of Cyprus. After several revisions, the plan was put to a referendum that year. While it was strongly supported by 65% of Turkish Cypriots, who were eager for reunification, only 24% of Greek Cypriots voted in favor. With this rejection, hopes for reunifying the island were effectively dashed.

I’m not sure what the future holds for Cyprus, but the three days we spent on this beautiful, historically rich eastern Mediterranean island were truly refreshing. While many people associate Cyprus with casinos and gambling, giving it the image of a small “sin city,” the island is so much more than that. Its past may still influence decisions for the future, yet we must remember that time moves on, and we cannot remain trapped by old wounds. What matters is striving for a better future, not just for ourselves, but for the generations to come.

Although Cyprus always seemed close enough to visit, spending a few days there made me realize how little I truly knew. Immersing myself in its culture and history was deeply fulfilling, and I hope our journey of learning and personal growth never ends. All of it, every step, every lesson, every interaction brings us closer to PEACE.